Hi, this is the part 2 of the New MS Exchange Attack Surface. Because this article refers to several architecture introductions and attack surface concepts in the previous article, you could find the first piece here:

This time, we will be introducing ProxyOracle. Compared with ProxyLogon, ProxyOracle is an interesting exploit with a different approach. By simply leading a user to visit a malicious link, ProxyOracle allows an attacker to recover the user’s password in plaintext format completely. ProxyOracle consists of two vulnerabilities:

- CVE-2021-31195 - Reflected Cross-Site Scripting

- CVE-2021-31196 - Padding Oracle Attack on Exchange Cookies Parsing

Where is ProxyOracle

So where is ProxyOracle? Based on the CAS architecture we introduced before, the Frontend of CAS will first serialize the User Identity to a string and put it in the header of X-CommonAccessToken. The header will be merged into the client’s HTTP request and sent to the Backend later. Once the Backend receives, it deserializes the header back to the original User Identity in Frontend.

We now know how the Frontend and Backend synchronize the User Identity. The next is to explain how the Frontend knows who you are and processes your credentials. The Outlook Web Access (OWA) uses a fancy interface to handle the whole login mechanism, which is called Form-Based Authentication (FBA). The FBA is a special IIS module that inherits the ProxyModule and is responsible for executing the transformation between the credentials and cookies before entering the proxy logic.

The FBA Mechanism

HTTP is a stateless protocol. To keep your login state, FBA saves the username and password in cookies. Every time you visit the OWA, Exchange will parse the cookies, retrieve the credential and try to log in with that. If the login succeed, Exchange will serialize your User Identity into a string, put it into the header of X-CommonAccessToken, and forward it to the Backend.

HttpProxy\FbaModule.cs

1 | protected override void OnBeginRequestInternal(HttpApplication httpApplication) { |

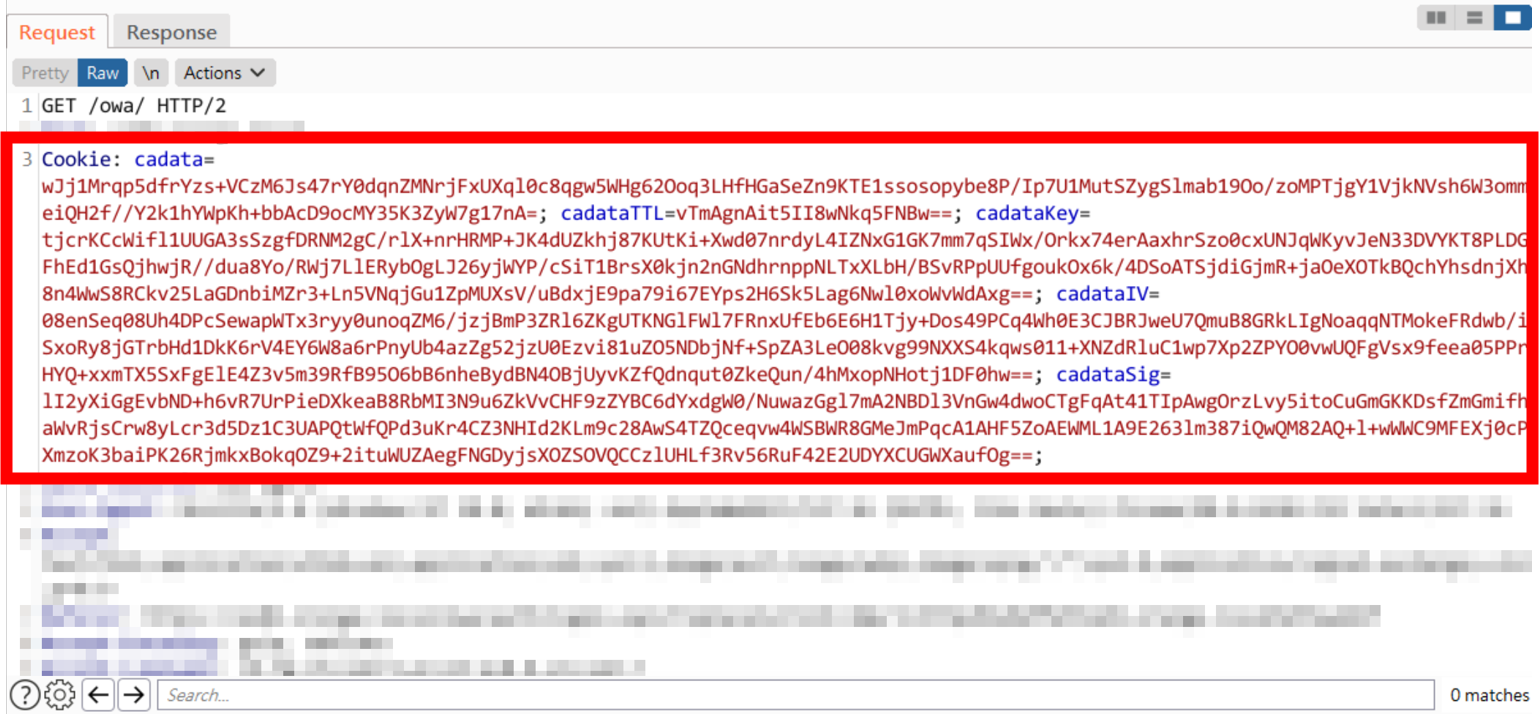

All the cookies are encrypted to ensure even if an attacker can hijack the HTTP request, he/she still couldn’t get your credential in plaintext format. FBA leverages 5 special cookies to accomplish the whole de/encryption process:

cadata- The encrypted username and passwordcadataTTL- The Time-To-Live timestampcadataKey- The KEY for encryptioncadataIV- The IV for encryptioncadataSig- The signature to prevent tampering

The encryption logic will first generate two 16 bytes random strings as the IV and KEY for the current session. The username and password will then be encoded with Base64, encrypted by the algorithm AES and sent back to the client within cookies. Meanwhile, the IV and KEY will be sent to the user, too. To prevent the client from decrypting the credential by the known IV and KEY directly, Exchange will once again use the algorithm RSA to encrypt the IV and KEY via its SSL certificate private key before sending out!

Here is a Pseudo Code for the encryption logic:

1 | @key = GetServerSSLCert().GetPrivateKey() |

The Exchange takes CBC as its padding mode. If you are familiar with Cryptography, you might be wondering whether the CBC mode here is vulnerable to the Padding Oracle Attack? Bingo! As a matter of fact, Padding Oracle Attack is still existing in such essential software like Exchange in 2021!

CVE-2021-31196 - The Padding Oracle

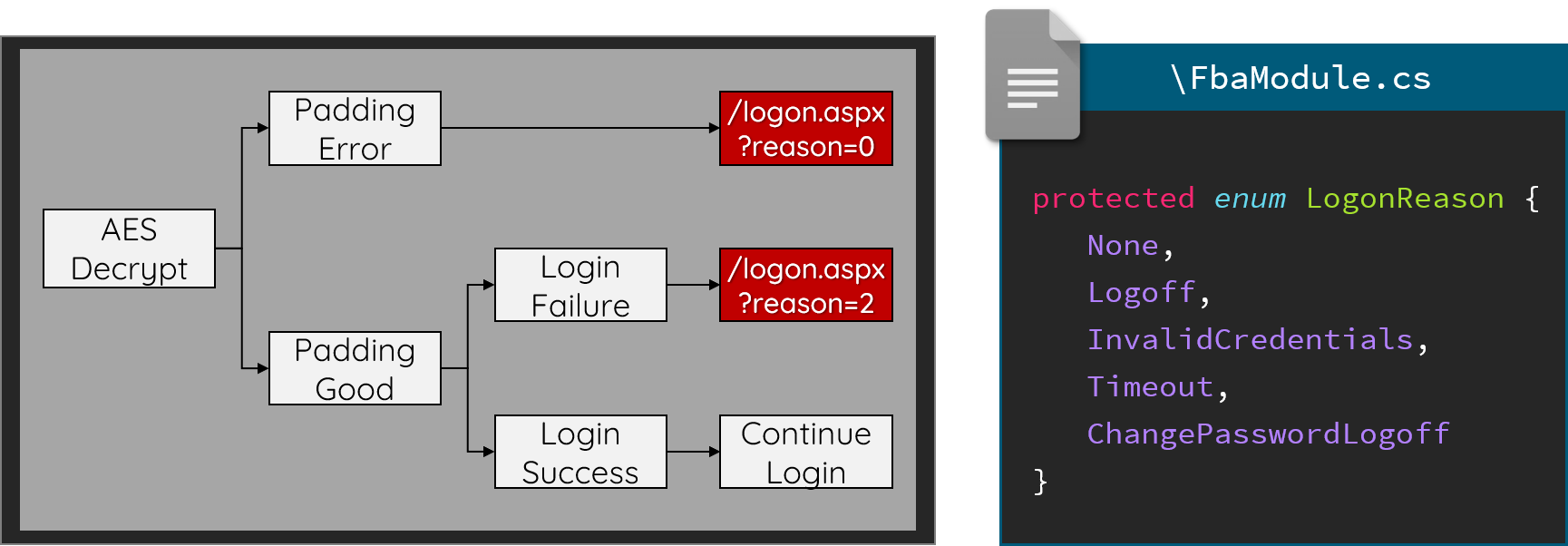

When there is something wrong with the FBA, Exchange attaches an error code and redirects the HTTP request back to the original login page. So where is the Oracle? In the cookie decryption, Exchange uses an exception to catch the Padding Error, and because of the exception, the program returned immediately so that error code number is 0, which means None:

Location: /OWA/logon.aspx?url=…&reason=0

In contrast with the Padding Error, if the decryption is good, Exchange will continue the authentication process and try to login with the corrupted username and password. At this moment, the result must be a failure and the error code number is 2, which represents InvalidCredntials:

Location: /OWA/logon.aspx?url=…&reason=2

The diagram looks like:

With the difference, we now have an Oracle to identify whether the decryption process is successful or not.

HttpProxy\FbaModule.cs

1 | private void ParseCadataCookies(HttpApplication httpApplication) |

It should be noted that since the IV is encrypted with the SSL certificate private key, we can’t recover the first block of the ciphertext through XOR. But it wouldn’t cause any problem for us because the C# internally processes the strings as UTF-16, so the first 12 bytes of the ciphertext must be B\x00a\x00s\x00i\x00c\x00 \x00. With one more Base64 encoding applied, we will only lose the first 1.5 bytes in the username field.

(16−6×2) ÷ 2 × (3/4) = 1.5

The Exploit

As of now, we have a Padding Oracle that allows us to decrypt any user’s cookie. BUT, how can we get the client cookies? Here we find another vulnerability to chain them together.

XSS to Steal Client Cookies

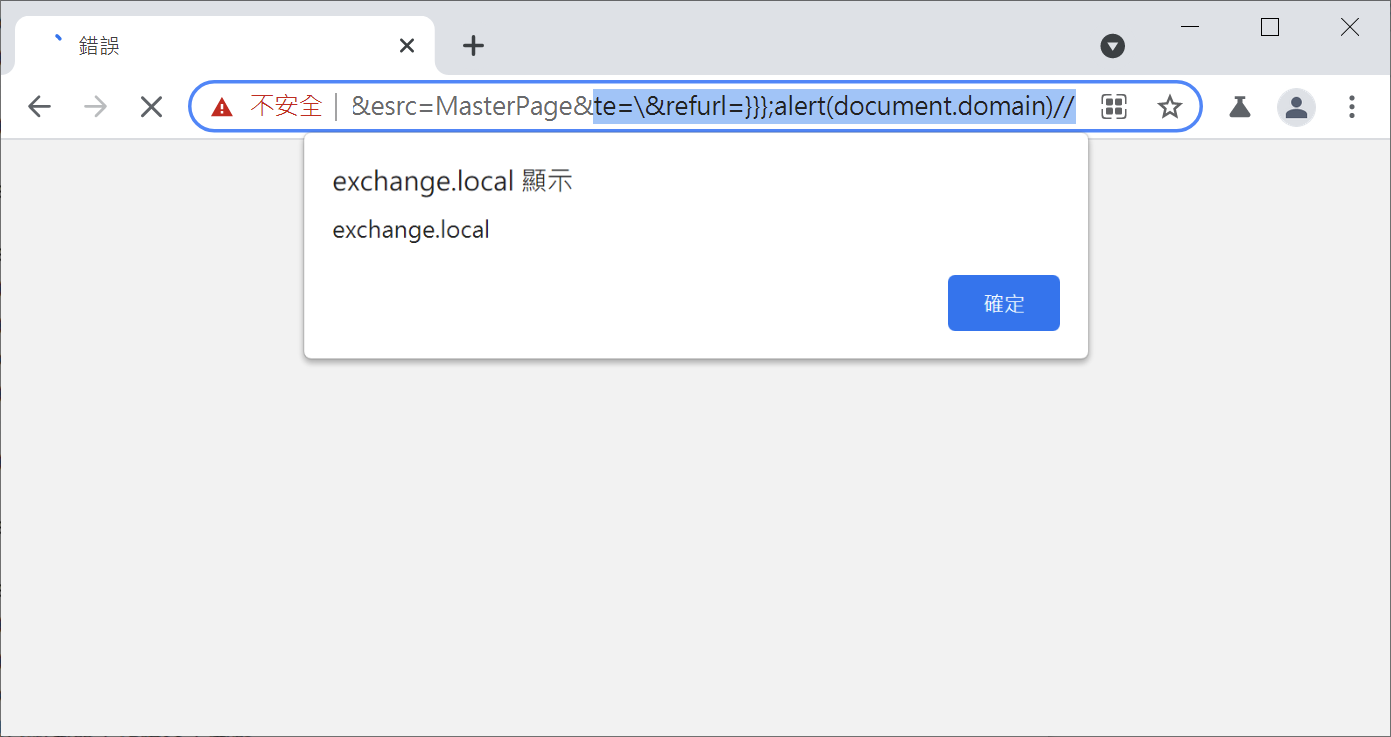

We discover an XSS (CVE-2021-31195) in the CAS Frontend (Yeah, CAS again) to chain together, the root cause of this XSS is relatively easy: Exchange forgets to sanitize the data before printing it out so that we can use the \ to escape from the JSON format and inject arbitrary JavaScript code.

1 | https://exchange/owa/auth/frowny.aspx |

But here comes another question: all the sensitive cookies are protected by the HttpOnly flag, which makes us unable to access the cookies by JavaScript. WHAT SHOULD WE DO?

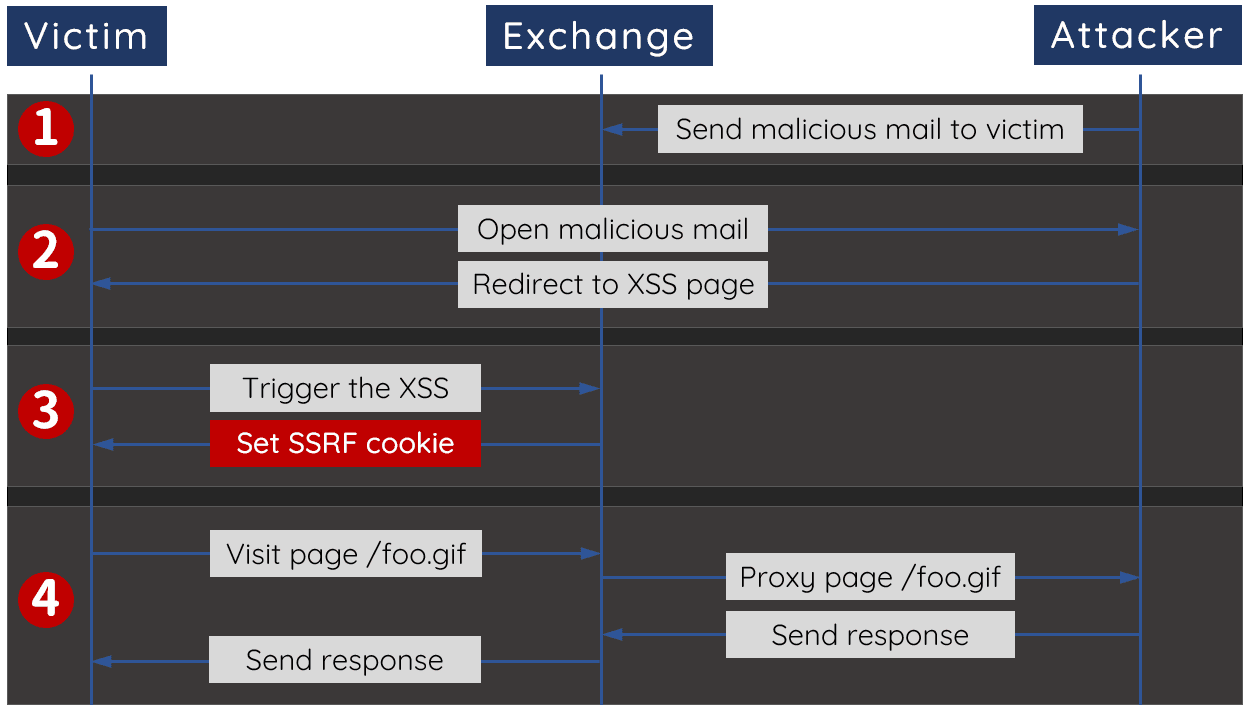

Bypass the HttpOnly

As we could execute arbitrary JavaScript on browsers, why don’t we just insert the SSRF cookie we used in ProxyLogon? Once we add this cookie and assign the Backend target value as our malicious server, Exchange will become a proxy between the victims and us. We can then take over all the client’s HTTP static resources and get the protected HttpOnly cookies!

By chaining bugs together, we have an elegant exploit that can steal any user’s cookies by just sending him/her a malicious link. What’s noteworthy is that the XSS here is only helping us to steal the cookie, which means all the decryption processes wouldn’t require any authentication and user interaction. Even if the user closes the browser, it wouldn’t affect our Padding Oracle Attack!

Here is the demonstration video showing how we recover the victim’s password: